“My past pads after me, paws on the flagstones,” thinks Cromwell, who builds new houses and watches old ghosts enter. We know our way around Cromwell’s home Austin Friars and what these walls have seen. Unlock the “room called Christmas” now and its past leaps out: this is where the doomed lutenist Mark Smeaton shrieked through the night among festive decorations that appeared, in his terror, as implements of torture. A spring lightly touched opens corridors into earlier books. But it also continues, deepens, and revises its forebears, negotiating with its past as does Cromwell with his.

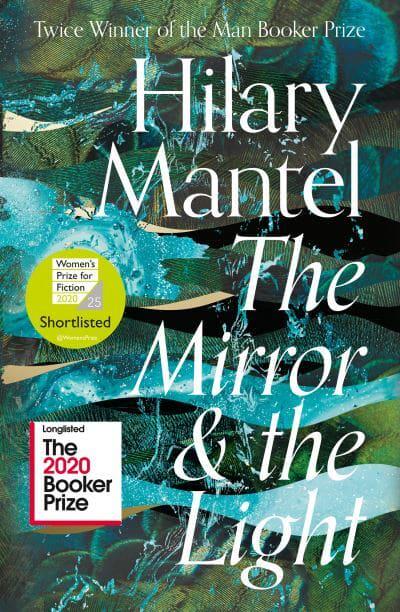

The Mirror & the Light is generously self-sufficient – to read this alone would hardly be skimping: it is four or five books in itself. Portrait of Sir Thomas Cromwell by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1532. This is what it’s like to be at the centre of power in Tudor England, and also a particular understanding of what it is, anywhere, to be alive.

“Scaramella’s off to war,” hums Cromwell, a tune from his Italian youth. Working with and against our foreknowledge, Mantel keeps us on the brink, each day to be invented. We see that the crowd dispersing after Anne Boleyn’s execution in the opening pages (“time for a second breakfast”) will gather again at its close. We can already tell the shape of this book. “The times being what they are, a man may enter the gate as your friend and change sides while he crosses the courtyard.” As for clothes, best try a reversible garment: “one never knows, is it dying or dancing?” Cromwell lives these years with henchmen at his back, and guards at every door.

Taking opponents in his grasp like the snake whose poisoned bite he once survived, he must manoeuvre his arch-enemies the Duke of Norfolk and Stephen Gardiner. He must reconcile Lady Mary to her father the king, bring down two of the most powerful families in Europe, turn monks into money, prevent imperial invasion, organise a new queen. Over four years, 1536-40, his tasks include the seemingly impossible. “But it’s useful wreckage, isn’t it?” and now Cromwell uses it, strenuously remodelling catastrophes as opportunities. Bring Up the Bodies closed with bloodshed and wreckage.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)